Race of the Century

Posted with permission from the Hamilton Spectator

_____________________________________________________

Looking back at the first Around The Bay Race

James Elliott

The Hamilton Spectator

March 26, 1994

If Billy Marshall were to run the course of tomorrow's Around the Bay Road Race, would he recognize anything?

When the winner of the inaugural marathon loped around the bay on Christmas Day, 1894, besting a field of 13 to win a $25 silver cup, Hamilton and Burlington were vastly different places than they are today.

Large stretches of the 30-kilometre (19-mile) course ran through rich farmland, most of the industrial complexes and high-speed transportation corridors that now define the bayshore didn't exist. And, undoubtedly, the waters of what was then called Burlington Bay were a lot cleaner.

And yet much of what the 24-year-old soldier/sportsman saw that clear, cold, windy day, endures.

Marking the original route today are several landmarks that guided runners a century ago, including some noted watering holes, a pioneer mansion, a nautical lighthouse and one of the first pumping stations in North America. When young Marshall came to the post as the class of a field of rank local amateurs, it's unlikely he realized he was launching a grand sports tradition unmatched in North America.

TURNED OUT IN CANVAS knickerbockers and tennis shoes. the72-kilo (160-pound) Marshall, a member of the Thirteenth Battalion (later to become the Royal Hamilton light Infantry), was an early favorite.

The streets surrounding the Opera house block on James Street North were lined. Despite the cold, windy weather and the fact it was Christmas morning, thousands lined the streets m James down to Barton and on to Sherman.

Over the next century, the race would attract fields that were much more illustrious—indeed, some of the best in the world would win in Hamilton, legendary figures like Longboat, Sherring and Caffrey—but it's doubtful any subsequent competitions could match that inaugural race for sheer exuberance and rowdy high spirits.

In addition to the thousands of onlookers who jammed the downtown start/finish, there were wild west cowboys, bicyclists and countless buggies strung out around the course. After a day of watching wagons run into bicycles run into racers, the Spectator reporter could only marvel at "such a congregation of crazy drivers and riders."

THE RACE ITSELF, sponsored by the feisty, upstart Hamilton Herald, Canada's original one-cent newspaper, was the brainchild of the paper's co-founding brothers, Robert and John Harris. Conceived on one of their regular Sunday morning walks around the bay, the brothers saw a chance to cash in on the burgeoning popularity of the 'sport papers were calling "pedestrianism".

A total of 29 "peds", including Robert Harris and members of several local athletic dubs, anted up the 50-cent entry fee for a chance at the $25 silver cup and three boxes of cigars put up as prizes.

By 9:30, Christmas morning, a bakers-dozen had assembled in the cold outside the Grand Opera House on James Street North. The bookmakers, Davis and Haskins, were still taking bets. Marshall and Harris were co-favorites at 3-to-l. Forty minutes later, when John Harris fired the starting gun, the field could barely move through the crush that spilled onto the course several blocks up James and along Barton as far as Sherman.

AS THE RUNNERS moved off, hundreds of young men jammed the trollies and followed behind, cheek and jowl with hundreds of horse-drawn rigs and men on horseback. Leading the parade, Tuckett's Mounted Scouts, sponsored by the local cigarette manufacturer and turned out in a wild west costume, cleared a path for the runners.

Clearly the organizers had no idea how wildly popular an around-the-bay footrace would be because contemporary accounts talk of spectators creating a spectacle that consistently overshadowed he race itself. Crowd control was virtually non-existent.

The Boxing Day edition of the Spec, while managing to avoid any mention of rival Herald as the sponsor, devoted nearly two columns of type to coverage, including a scathing indictment of vehicular deportment.

"Never at any one time had there been such a congregation of crazy drivers and riders congregated in Hamilton. From the start of the race to the finish, complaints were numerous and bitter as to their conduct.

"The mounted patrol endeavored to make of itself a mounted cowboy aggregation racing and running wild over the entire course. Drivers of rigs (buck-boards) were no less foolish and several accidents were reported."

On the Beach Strip, the city's truant officer was amazed to see another buggy drive up and over his rig, "considerably damaging his slash board. The driver of the intruding vehicle whipped up his horse and went on without waiting to explain or apologize." The second who was leading Marshall on his wheel near the Valley Inn "was run down by a furiously driven rig and his wheel badly smashed. He was thrown in the ditch and escaped injury." A bicyclist, following the racers, collided with a horse near Sherman and Barton. "The shock knocked him off his wheel and in front of a passing buggy which ran him over. He was badly bruised and cut," the newspaper reported. At the Valley Inn, a man ran out in the road to shake Marshall's hand and was promptly run over by the bicyclist who was pacing the runner.

As for the race itself, the Harris brothers had worked out the around-the-bay route — estimated at 19 or 20 miles — as an arduous blend of town and country terrain.

Barton Street downtown, today retains much of the late 19th Century style, though the tinsmiths and glass-blowers have been replaced with secondhand shops and pizzerias. In 1894, there wasn't much east of Sherman until the racetrack— now replaced by the Centre Mall — and the Jockey Club which survives today as the Oakwood. Turning north at the Jockey Club, the open fields now house the towering stacks and giant green plumbing of the mighty Dofasco complex. This is pure Hamilton. Unapologetic, unvarnished. Tough, gritty and definitely not pretty. At Woodward Avenue, the cut-stone grandeur of Thomas Keefer's pumping station is still imposing but now shares the neighborhood with the mountainous beige and charcoal slag heaps, incidental harvest of the steel industry.

Under the QEW, the lake now in sight, discourse turns onto the Beach Strip, a little worse for wear but still possessed of considerable charm, to pass Dynes' Hotel.

There's a heavy soft coal smell in the air, and the old tavern's now sheathed in grey siding and sports a monster satellite dish, but in the roadside grass nearby there's concrete evidence of another era — a tumbledown stone marker bearing the legend "HERALD — 5-M-V".

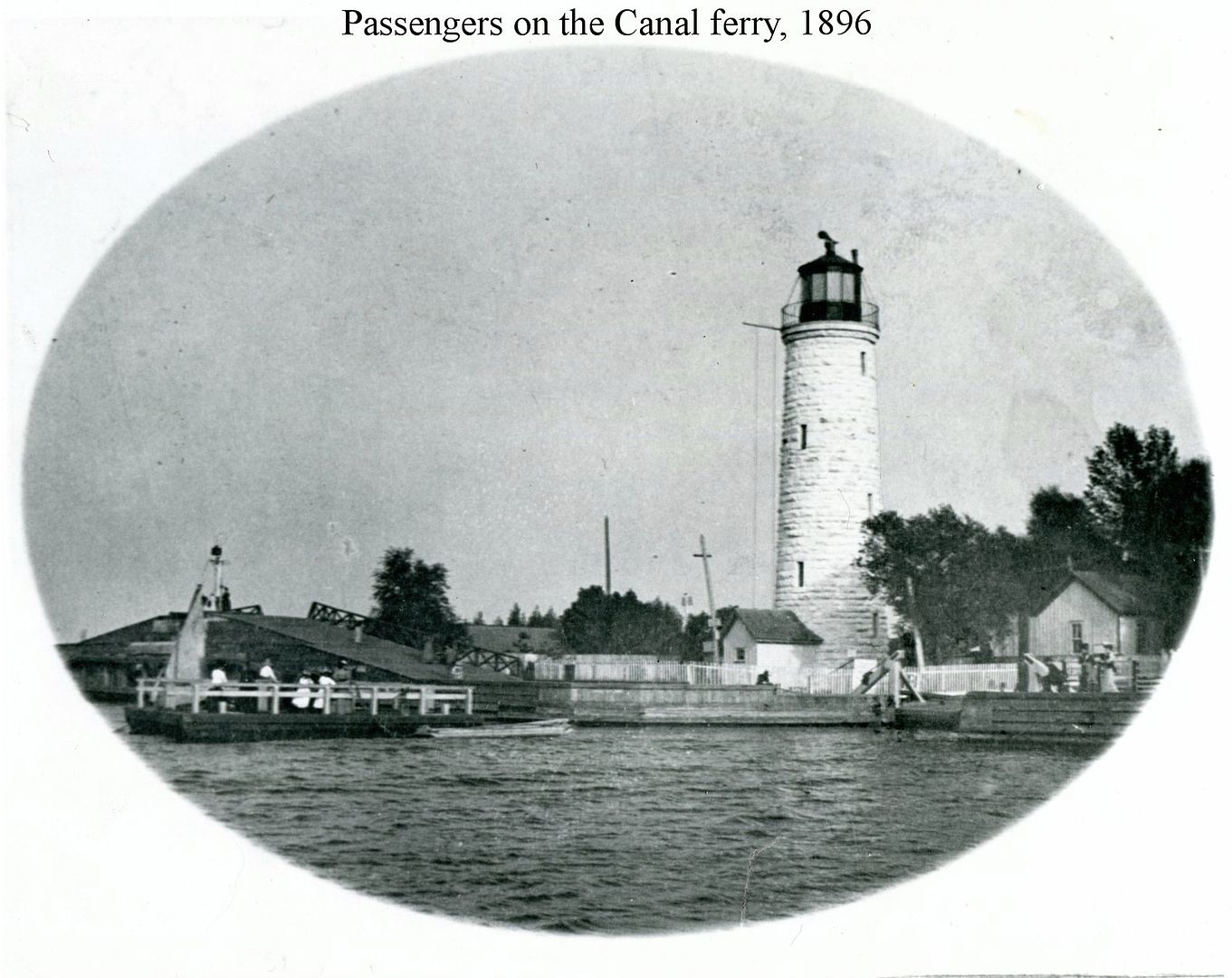

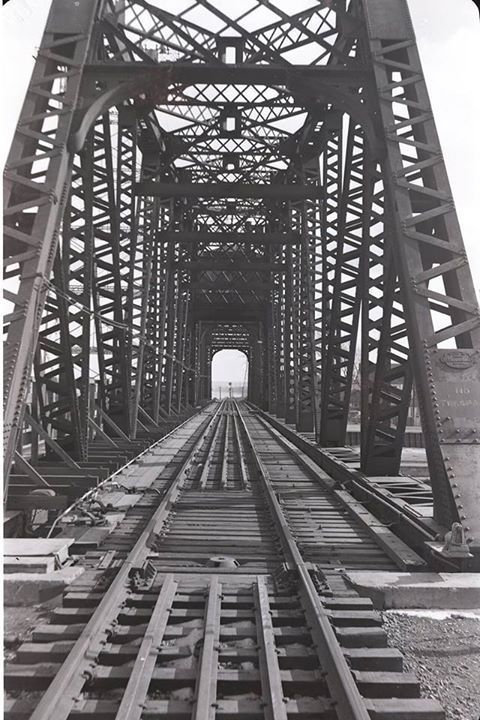

The strip's permanently in the shadow of the Skyway but there are still hints of faded elegance in the surviving homes that attest to an age when the Beach was a place of leisure and high style. IN THE BEGINNING, runners got to cross the ship's canal on the railway bridge, everyone else got to cross with the ferryman and admire the stone canal lighthouse. At the end of the Beach Strip, Joseph Brant's 18th Century landmark house is gone but a lookalike museum stands nearby looking a bit lost in the midst of a hospital complex.

The rolling farmland of a century ago has been replaced by malls, rows of town housing, gas stations and convenience stores. The course today winds through affluent Burlington neighborhoods down past the park where Robert Cavalier de la Salle visited 325 years ago.

At the 16-mile point, the course follows the original route dropping down to the Valley Inn, across the noisiest small bridge in the province. To climb Heartbreak Hill on the other side to York Boulevard, across the High Level Bridge unto Burlington Heights and the postcard perspective of the bay. In 1894, when Billy Marshall broke away from the field and came down York alone leading dozens and buggies and bicycles, he was cheered by mass crowds all the way downtown. His time was two hours and 14 minutes. Described in the Spec as "hard as nails," Marshall turned up at a victory banquet that night to accept the silver cup. Place and show got boxes of cigars.

AS A LAST WORD, the Spec wrapped up the inaugural race with an observation that has "So successful was the

event that the race will likely be run annually. By donating the cup, the promoters of this race have created an interest in go-as-you-please races, which will not die out for some time." Indeed it will not.

/https://www.thespec.com/content/dam/thespec/life/local-history/spec175/2021/04/03/tom-longboat-won-around-the-bay-in-1906-then-boston-marathon-a-year-later/boston.jpg)