I'm sure many of you have heard this old story from the War of 1812, the British fleet is fighting it out on the lake with the Americans near what is now Toronto and after some damage, decides to head to Hamilton Harbour (Burlington Bay) for cover.

This story has been written and rewritten many times in various history books, has it's own Provincial plaque dedicated to it's honour located in Harvey Park, not far from Dundurn Castle. This great moment in Canadian history even has many beautiful paintings brushed in it's memory. The problem is that this story is probably nothing more than that, a story.

Examples;

From: Harbour Lights-Burlington Bay by Mary Weeks-Mifflin & Ray Mifflin

"A nor'easter was blowing, the seas were rising, and the British flagship Wolf was struggling, her top main mast sheared off. The year was 1813 and Chauncey's American squadron was in pursuit. The "Burlington Races" had begun.

British commander Sir James Yeo signalled to the corvette Royal George, the brigantine Prince Regent, and the trio of schooners which followed, that they were heading for refuge at Burlington Bay, even though it was landlocked by a long, sandy beach. Only a shallow creek, known locally as the "Outlet," provided any entrance to the harbour, and there was a great risk that the 426-ton Wolf would be driven ashore.

Oddly enough, it was the gale that saved them. It had piled up the waters at the head of Lake Ontario and scoured a passage through the bar, allowing the squadron access. The American fleet chose to break off pursuit and head for the safety of Fort George, since a reconnaissance party in July of that year had revealed the shallowness of the Outlet.

The British had been lucky and they knew it. Had the engagement lasted a few hours longer, only the seaman's lantern hoisted on the flagpole by the blockhouse at the Outlet would have provided any aid for Yeo's young

navigator, Richardson."

From: Hamilton: An Illustrated History by John C. Weaver

The final local encounter was a naval engagement that began near York on 18 September 1813. After an hour of indecisive action, British Commodore Sir James Yeo broke off to avoid the growing superiority of the American squad-ron. In heavy winds, he made a run for Burlington Bay. With the storm waves adding depth to the channel at Burlington Beach and having aboard a youth familiar with the local waters, Yeo escaped into the bay.

From: Pathway to Skyway-A History of Burlington by Claire Emery.

The two fleets met in action in September of 1813. Sir James had landed supplies at the head of the lake and returned to York. The next day the American squadron of 11 ships appeared off shore and against this force Sir James mustered two corvettes, a brig, and three schooners. The Americans had more and heavier guns and, while staying out of range, battered the British squadron without having a shot fired near them in return.

Although Sir James was out-gunned and out-ranged, he put out to give battle off the present Canadian National Exhibition grounds at Toronto. Just after noon, Sir James broke off the action because his ship had suffered severely and a gale was coming up. The rest of the American ships were beginning to arrive so he decided to make a run for it to the head of the lake. This was referred to later by the British sailors as the "Burlington Races."

About five o'clock in the afternoon, riding the high water that was raised by the storm that day, the British entered what is now Hamilton Harbour, through a narrow channel near Brant House. Once inside the bay, Sir James' problem was to get out again, without Chauncey blocking him.

Photo # 1 Provincial Plaque at Harvey Park

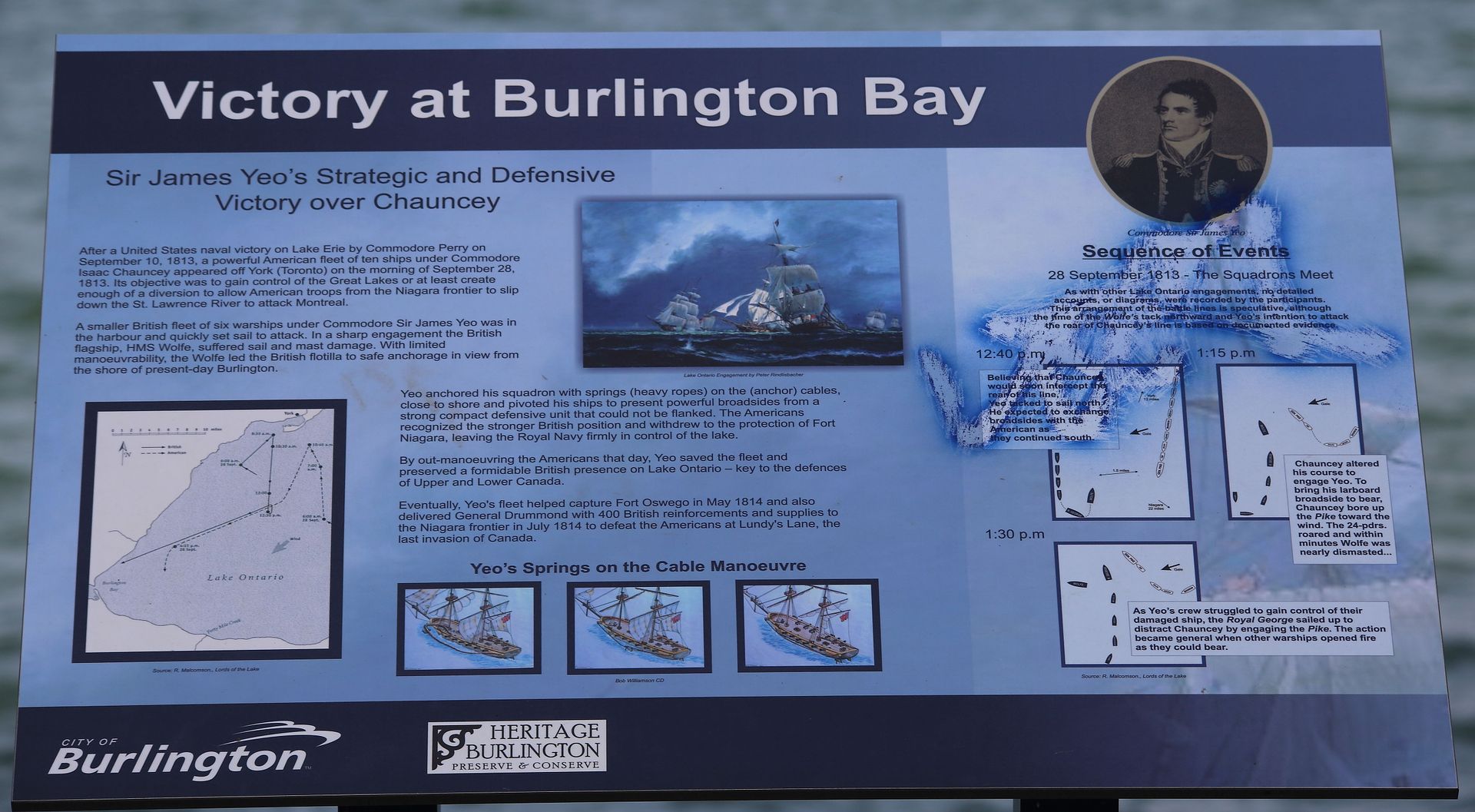

Photo # 2 & 3 The Burlington Races paintings by Peter Rindlisbacher, All rights reserved, the Hamilton-Scourge Foundation

This story has been written and rewritten many times in various history books, has it's own Provincial plaque dedicated to it's honour located in Harvey Park, not far from Dundurn Castle. This great moment in Canadian history even has many beautiful paintings brushed in it's memory. The problem is that this story is probably nothing more than that, a story.

Examples;

From: Harbour Lights-Burlington Bay by Mary Weeks-Mifflin & Ray Mifflin

"A nor'easter was blowing, the seas were rising, and the British flagship Wolf was struggling, her top main mast sheared off. The year was 1813 and Chauncey's American squadron was in pursuit. The "Burlington Races" had begun.

British commander Sir James Yeo signalled to the corvette Royal George, the brigantine Prince Regent, and the trio of schooners which followed, that they were heading for refuge at Burlington Bay, even though it was landlocked by a long, sandy beach. Only a shallow creek, known locally as the "Outlet," provided any entrance to the harbour, and there was a great risk that the 426-ton Wolf would be driven ashore.

Oddly enough, it was the gale that saved them. It had piled up the waters at the head of Lake Ontario and scoured a passage through the bar, allowing the squadron access. The American fleet chose to break off pursuit and head for the safety of Fort George, since a reconnaissance party in July of that year had revealed the shallowness of the Outlet.

The British had been lucky and they knew it. Had the engagement lasted a few hours longer, only the seaman's lantern hoisted on the flagpole by the blockhouse at the Outlet would have provided any aid for Yeo's young

navigator, Richardson."

From: Hamilton: An Illustrated History by John C. Weaver

The final local encounter was a naval engagement that began near York on 18 September 1813. After an hour of indecisive action, British Commodore Sir James Yeo broke off to avoid the growing superiority of the American squad-ron. In heavy winds, he made a run for Burlington Bay. With the storm waves adding depth to the channel at Burlington Beach and having aboard a youth familiar with the local waters, Yeo escaped into the bay.

From: Pathway to Skyway-A History of Burlington by Claire Emery.

The two fleets met in action in September of 1813. Sir James had landed supplies at the head of the lake and returned to York. The next day the American squadron of 11 ships appeared off shore and against this force Sir James mustered two corvettes, a brig, and three schooners. The Americans had more and heavier guns and, while staying out of range, battered the British squadron without having a shot fired near them in return.

Although Sir James was out-gunned and out-ranged, he put out to give battle off the present Canadian National Exhibition grounds at Toronto. Just after noon, Sir James broke off the action because his ship had suffered severely and a gale was coming up. The rest of the American ships were beginning to arrive so he decided to make a run for it to the head of the lake. This was referred to later by the British sailors as the "Burlington Races."

About five o'clock in the afternoon, riding the high water that was raised by the storm that day, the British entered what is now Hamilton Harbour, through a narrow channel near Brant House. Once inside the bay, Sir James' problem was to get out again, without Chauncey blocking him.

Photo # 1 Provincial Plaque at Harvey Park

Photo # 2 & 3 The Burlington Races paintings by Peter Rindlisbacher, All rights reserved, the Hamilton-Scourge Foundation

Attachments

-

116.2 KB Views: 156

-

349.6 KB Views: 138

-

88.2 KB Views: 129

Last edited: