Posted with permission from the Hamilton Spectator

______________________________________________________________________

New chemical being added to Hamilton drinking water treatment

The city is adding orthophosphate to the drinking water to reduce corrosion in the city’s remaining old lead pipes in the water distribution system.

October 30th, 2018 by

Carmela Fragomeni The Hamilton Spectator

Treatment tanks in the orthophosphate water treatment facility. - Gary Yokoyama,The Hamilton Spectator

The view from the top of the methane storage ball tank. Below Hamilton’s water treatment facility spreads out. - Gary Yokoyama , The Hamilton Spectator

Andrew Grice is the director of Hamilton Water. He is in the facility’s original control room. These controls are no longer in use. - Gary Yokoyama , The Hamilton Spectator

A rare view from the top of Hamilton’s famous methane storage ball tank. - Gary Yokoyama , The Hamilton Spectator

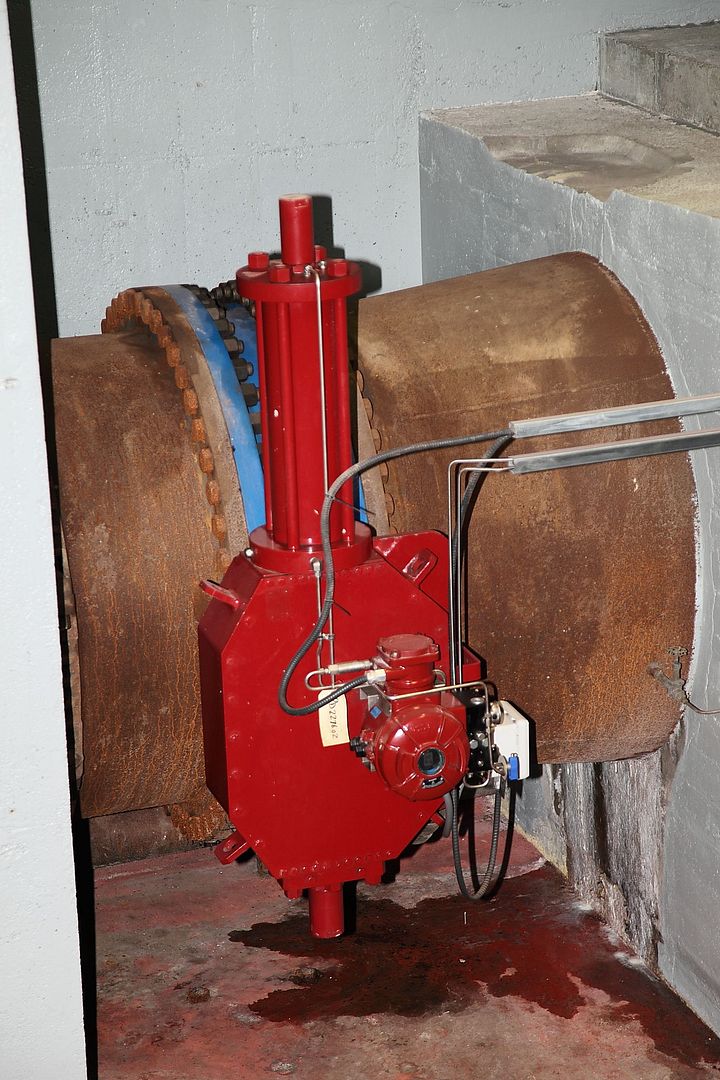

Interior view of the orthophosphate water treatment facility. - Gary Yokoyama , The Hamilton Spectator

The control room of the orthophosphate water treatment facility. - Gary Yokoyama , The Hamilton Spectator

Exterior view of the orthophosphate water treatment facility. - Gary Yokoyama , The Hamilton Spectator

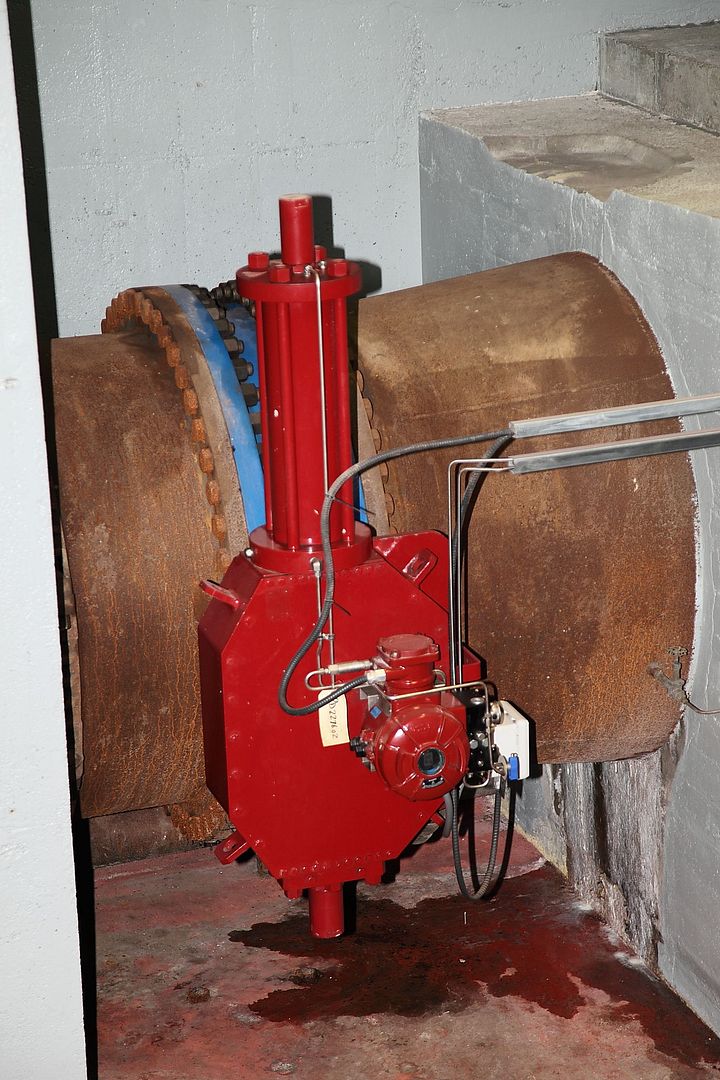

High-lift pumping station interior with six 1700 HP pumps used to push treated water to the reservoirs. - Gary Yokoyama , The Hamilton Spectator

1 / 8

Around Nov. 7, the city is adding another chemical besides chloride and fluoride to your drinking water.

It's orthophosphate, and its purpose is to adhere to pipes as a protective coating your drinking water passes over on its way to your home tap. But some of it will end up in your glass of water.

Why is it needed?

An average person would need to drink 330 glasses of water to get the same amount of phosphate that is in one glass of milk.

To control corrosion on the remaining old lead pipes in the water distribution system. Orthophosphate is one of the most common methods used for control, says Andrew Grice, director of Hamilton Water.

This is needed because the lead that corrodes and leaches into the drinking water from lead pipes is bad for people.

"Consumption of even very small amounts of lead is harmful to human health, especially in infants, young children, and pregnant woman," said Grice in a report to council last month. "There is no recommended level of lead ingestion that is considered safe."

Treatment tanks in the orthophosphate water treatment facility. | Gary Yokoyama , The Hamilton Spectator

OK, but is orthophosphorus safe?

Yes, according to the city.

It is a form of phosphorus — and phosphorus, found in human bones and teeth, is an essential mineral for growth and repair of body cells. We need it, in low levels, to survive.

Orthophosphate is being added on or around, Nov. 7, depending on equipment checks, in the form of food-grade phosphoric acid that is a clear, odourless liquid.

By the time drinking water reaches your tap, "only a minimal amount remains," says Grice.

An average person would need to drink 330 glasses of water to get the same amount of phosphate that is in one glass of milk.

Exterior view of the orthophosphate water treatment facility. | Gary Yokoyama , The Hamilton Spectator

Do other cities do this?

Yes. Orthophosphate is used in Toronto, Winnipeg, Halifax, New York City, Detroit, Chicago, and Washington, D.C., among others.

The United Kingdom started treating water with it over 30 years ago. It is now used in 95 per cent of drinking water systems there.

Interior view of the orthophosphate water treatment facility. | Gary Yokoyama , The Hamilton Spectator

But why not just replace old lead pipes?

Any lead water mains that existed have been replaced. But the city is still replacing pipe connections to private properties ad hoc. And unless homeowners have replaced their own incoming lead pipes in homes built before the mid-1960s, they exist there too.

What else is added to our drinking water?

Chlorine, fluoride, aqueous ammonia and poly aluminum chloride.

Chlorine disinfects and kills harmful bacteria. Fluoride reduces tooth decay, and aqueous ammonia keeps the chlorine from losing its power as it goes through the distribution system.

High-lift pumping station interior with six 1700 HP pumps used to push treated water to the reservoirs. | Gary Yokoyama , The Hamilton Spectator

Is that it, for making drinking water safe?

No. It's more involved than that, but put simplistically:

Water is drawn from an intake pipe in Lake Ontario, 900 metres offshore from near Barangas on the Beach restaurant on Van Wagner's Beach Road. A chlorine injection is given as needed in summer to prevent lake zebra mussels from clogging the intake pipe.

The lake water is drawn into a "low lift" pumping station building across from Hutch's restaurant, also on Van Wagner's Beach Road. A large screen captures debris coming in with the water.

Then a pipe going under the Queen Elizabeth Way carries the water to the treatment plant on Woodward Ave. Poly aluminum chloride is added to bind particles like clay, silt, sand and bacteria so they sink into sediment tanks.

Hamilton's drinking water treatment plant is on the same site — but on opposite ends — as the main sewage treatment plant which discharges into Hamilton Harbour near the Windemere Basin.

Once clay and other particles settle out, the lake water is moved through filter basins where carbon filters, acting much like a Brita filter, remove organic material, improve taste and eliminate odour.

Once passed the filters, the water goes into clearwells (large underwater storage tanks). It is at this point that chlorine is added, then fluoride — and coming soon, orthophosphate.

As the treated water is then pumped out, aqueous ammonia is added to help the chlorine stay in the system.

The water is sent out through high lift pumps and distributed to 21 water pumping stations, 13 reservoirs, and seven water towers throughout the city before ending up at household taps.

The city's water system of pipes, reservoirs and water towers amount to an asset of $3.2 billion.

Drinking water enters the distribution system through a series of large pipes ranging in diameter from 1,200 mm (48 in.) to 2,250 mm (88 in.)

The water treatment plant can treat up to 909 megalitres per day, the equivalent of 350 Olympic swimming pools.

Andrew Grice is the director of Hamilton Water. He is in the facility's original control room. These controls are no longer in use. | Gary Yokoyama , The Hamilton Spectator